Twice More to the Lake. Once With E.B White, once With My Kids.

“We rowed a wooden boat out into the middle of the lake and sat there all afternoon.

Then we rowed back.”

My daughter Sandra as age 15.

It was a lot more exciting than that.

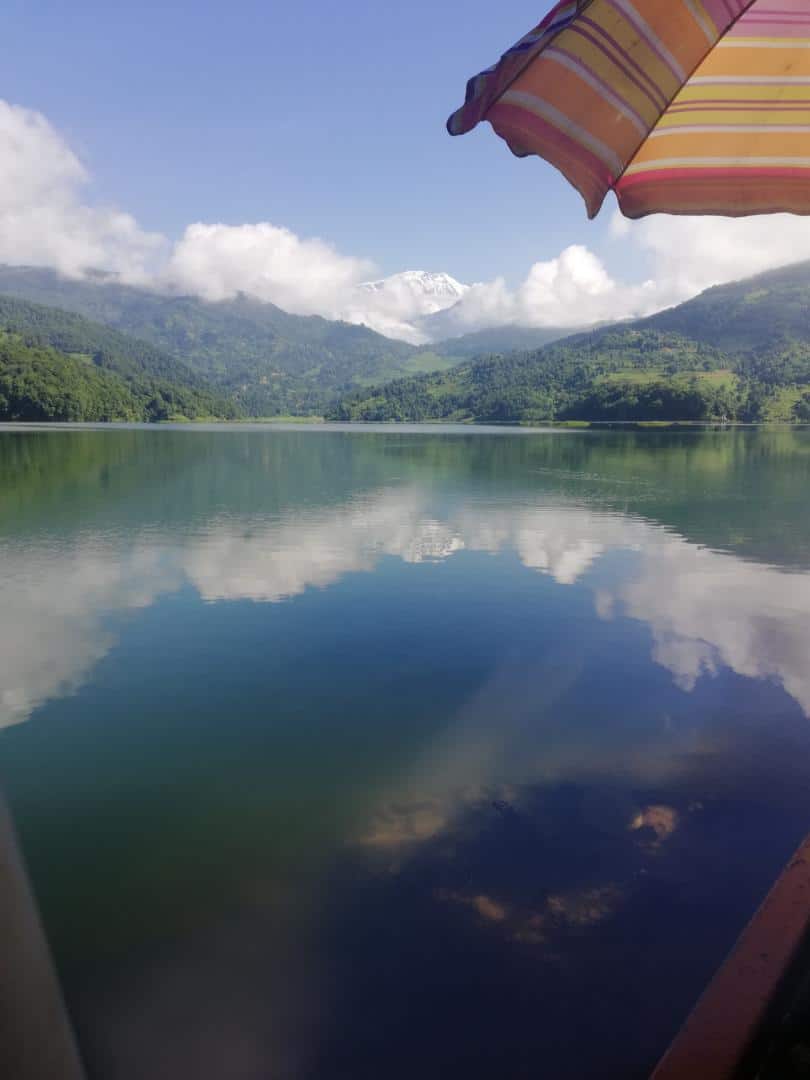

When boating in Pokhara, the tourist heart of Nepal, you have two options. Bengas Lake and Phewa Lake. Phewa is in town and offers more options in terms of watercraft. Phewa (or Fewa, depending on how you want to transliterate the Nepali alphabet) has rowboats and pedal boats and paddleboats and pontoons, two-seaters and four-seaters and even eight-seaters so your whole party can party.

On Begnas, we have a few rowboats. You can put a whole family of locals into one, or two tourists and a gondolier. Okay, okay, not a gondolier. Most likely it’ll be my buddy Sanu, with a wooden paddle.

Sanu hates rowing.

But he’s a professional at accommodating tourists and other lovers of the natural and the outdoors, so he’ll hide his discomfort (his shoulders usually hurt from swimming) and paddle you around at sunrise or sunset, for, of course, a nominal fee.

Once he knows you well enough- this takes about forty minutes- he’ll let you out on your own, so he doesn’t have to row. This way, you can enjoy nature on your own, or with your fifteen-year-old daughter.

The Rowboat

We are here for the small things. Today we are here for the simple. So, we are in the simplest watercraft possible. It’s a rowboat, Sandra was right about that. The inside is painted bright yellow; it is one of the only things around this lake that has a fresh coat of paint.

Getting here was exciting enough (have you read about our bus rides? “The Paraglider and the Goat”), the bus is always a wild adventure. Now that we are at the lake, at the foot of the mountain, so imposing, so immobile, and so rarely seen, we are here for peace. So dedicated are we in our pursuit of quiet, we have left my wife and son, both incorrigible chatterboxes, on the shore, waving at us.

My son is a champion waver.

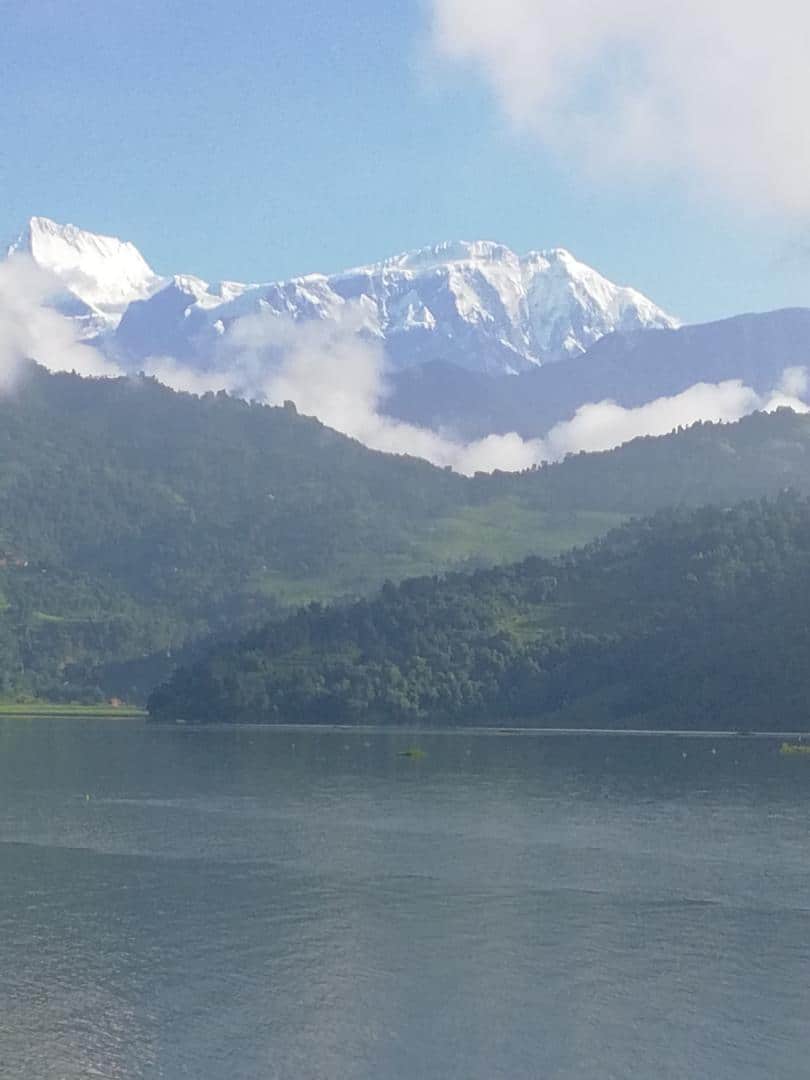

The land around Begnas Lake is rolling and hilly, a portal to the mountains beyond. These are a galaxy unto themselves… They are far away. They are the subject of future features.

I am here with my daughter, who has never seen snow. She’s never had fresh water up her nose, either. Over the past two or three years, she’s never seen much outside of the Galaxy Smartphone. That is a pretty small world, despite it being a galaxy.

Today we are in search of the small. Today we are in search of life at insect speed. There are dragonflies everywhere out here; they thrive in this climate – the wettest part of the year. They are hearty, and unlike me, do well at altitude. As we row, I am envious of them. They move much easier across the surface of the lake than I do.

The Beauty

I understand that as a writer it is my job to describe things to you. Here I am a failure at my job. The beauty here stuns me like a heart punch. Any photographer who claims to have captured it is lying to you. They will try to show you proof to convince you otherwise (as I am about to) but do not believe them, no matter how many pictures of mountains they show you on their phones.

Here are some exciting things that happened to us on our “boring trip:”

A purple and black butterfly landed on my shoulder. Things like this do not happen; the natural world is a cruel place, indifferent to our notions of beauty or our desires for connection with a world beyond our own.

I saw a fish. We did not see any leopards, although I am told they lurk in the jungle, just out of the range of our vision. There were monkeys, family after family of rhesus macaques, but we’ve seen so many monkeys that we are as indifferent to them as they are to us. Getting excited about monkeys marks you as a tourist, a newbie, a rube.

I am a rube.

Not all, I’m sure, was as magical as it seemed at the time. Most of it could have been as banal and as boring as Sandra claimed. For example, the butterfly landed on a lot of things; my shoes, the port side of the boat (which I am told is left). We were in a small boat in the middle of the lake; I’m sure it needed a rest.

Once More to the Lake

I am reading through a series of classic pieces of outdoor writing. First published in Harper’s magazine in 1941, “Once More to the Lake” narrates White’s visit to Belgrade Lakes in Maine and is a perfect place to start, especially since, well, we’re on the lake. It’s a story about manhood; growing into it and growing out of it.

There is a paragraph from White that encapsulates this theme with such elegance and grace it takes the breath away, like dipping into cold water.

“We stared silently at the tips of our rods, at the dragonflies that came and wells,” White begins, and I note the dragonflies darting about the surface of the water around us.

“I lowered the tip of mine into the water, tentatively, pensively dislodging the fly, which darted two feet away, poised, darted two feet back, and came to rest again a little farther up the rod. There had been no years between the ducking of this dragonfly and the other one–the one that was part of memory.”

Breathe. Concentrate. Hear all that at insect speed.

Since Sandra won’t take her headphones off, I put mine on. She is listening to a K-pop group whose name I cannot pronounce, I am listening to 13 and God. I’m not sure where they are from, but I promise it isn’t Seoul. They sing:

“Come time is too slow

This is insect speed

This is insect speed.”

I watch the dragonflies. I row and I swim for a while, because these are the things we do when we’re trying to slow our lives down, these are the things we do when we are once more at the lake.

As Sandra and I sit in the boat, the lake so still and silent that we’re not even drifting, I read to her. Now that her phone battery has died, she is kind enough to take her ear buds out while she stares at the mountains and the teeming jungle below them. Below the mountains, but above us here on the lake, growing there is equipoise.

I have her attention for the moment, so I continue. I have White on actual paper in an old-fashioned book, so unlike my daughter, my entertainment is not battery-dependent.

“My boy loved our rented outboard, and his great desire was to achieve single-handed mastery over it, and authority, and he soon learned the trick of choking it a little.”

As for the boy still waving on shore, he is not yet of an age where mastery of machines is an issue of self-worth and masculinity; he is still at an age where machines are magic and mesmerizing. Once a dump truck or a cement mixer gets rolling, he is no more capable of looking away than he is of stopping his breath.

“But now the campers all had outboards. In the daytime, in the hot mornings, these motors made a petulant, irritable sound; at night, in the still evening when the afterglow lit the water, they whined about one’s ears like mosquitoes.”

We need to stop a moment here and meditate on quiet.

A lake without motors

If you are reading this blog, you are an outdoorsy sort. People of the trail and the water. Lake folks. Growing up in northern Minnesota, the lake was the center of life. As was boating. The addition of motors changes your experience at the lake in profound ways.

I am no mystic. But there is something almost transcendental about the quiet of a lake without motors. A re-evaluation of our relationship to loud, powered boats and other watercraft may not be possible; it is much easier to give people freedoms than to take them away. This is, however, unfortunate.

“Much machines on every fast

Like time’s too slow

This is insect speed.”

I row us home. I understand now why Sanu does not like it. My shoulders are achy and my skin is red and will need a slathering of aloe. Showers and a dinner of daal bhat and black tea are called for.

After dinner, I read White once more to my wife and my son. I hope Sandra is listening but I know she is underneath her headphones; at fifteen while my dad was reading some old claptrap, I certainly would have been.

I’m a salt-water man

We have nowhere to start a campfire yet, although this is a problem we are fixing with the utmost of haste. So tonight we have lit candles and stuffed them into the open necks of empty (and not quite empty) bottles of Fanta and Everest, a local beer which is far, far too strong for me to try at any altitude, much less this one.

I start, looking for a place that will catch the interest of my wife, whose English is limited, and my son, whose English is in that incomprehensible zone known only to toddlers and savants.

“We all got ringworm from some kittens,” I begin. Everybody understands and loves kittens, right? “We had to rub Pond’s Extract on our arms and legs night and morning, and my father rolled over in a canoe with all his clothes on.”

My wife laughs at this. I’ve hooked her, so far. I got ringworm from a cow. That isn’t nearly as poetic. And my father was always aces with the canoe.

“I have since become a salt-water man, but sometimes in summer there are days when the restlessness of the tides and the fearful cold of the sea water and the incessant wind which blows across the afternoon and into the evening make me wish for the placidity of a lake in the woods.”

A lake like Begnas.

I do not take to salt water. It spits me out. The worst days of my life have been spent next to the ocean and I blame the ocean entirely. The lake? Oh the lake is kinder to me; the lake reminds me that nature can be gentle and indifferent simultaneously. That my life and my problems are small in the face of the Himalayas across the water. And that life will, sooner or later, slow down to insect speed.

My family is drowsy; my boy lays across my lap in that border state between awake and sleep, between this conscious and physical world and the dreamy, ethereal next one. I continue my bedtime story, feeling the end coming near. I read what may be the best sentence in all of American literature.

“He pulled his dripping trunks from the line…I watched him, his hard little body, skinny and bare, saw him wince slightly as he pulled up around his vitals the small, soggy, icy garment. As he buckled the swollen belt suddenly my groin felt the icy chill of death.”

I am grateful for everything the lake has given us, every boring moment, every butterfly that I saw, every leopard my daughter did not see. Now that I have been blessed with kids to remember all of this, I will even be grateful for the icy chill of death, so long as it comes for me at insect speed.